Ultra-Indie Spotlight: To Dawn And Back Explores The Horror In The Mundane

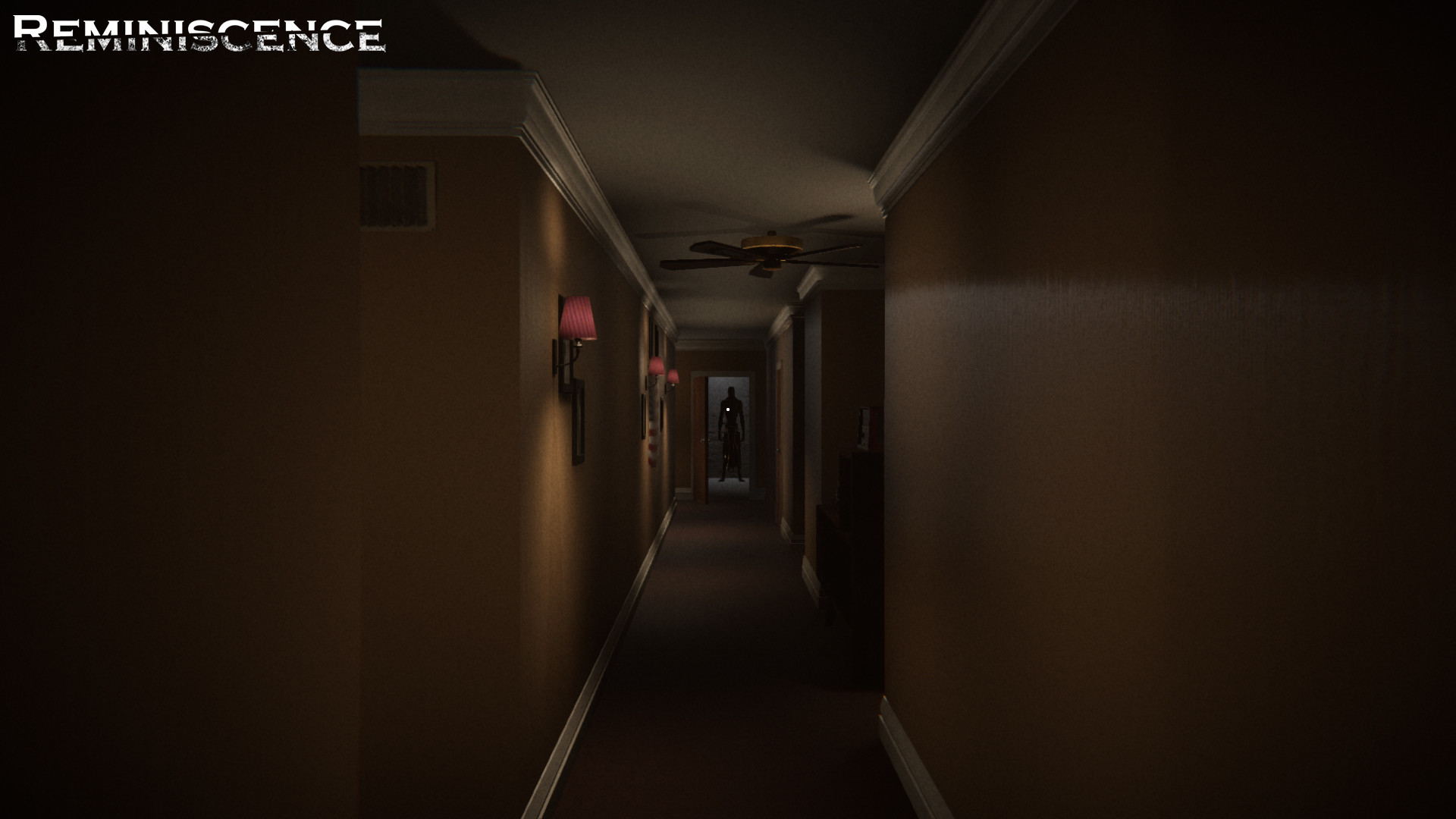

To Dawn and Back is an “experimental first-person horror game” by indie dev Pagan Black. It’s a story about a child who moves into a city to live with his aunt. The city is under the heavy rule of a religious sect known as The Sisters. Similar to Postal 2, you kind of just go about your day, talking with people in the town, before returning to your apartment. Eventually, the game has you “explore the spaces between dreams and memories,” though I can’t really explain more than that, because To Dawn and Back is extremely surreal. It’s mostly a series of abstract worldbuilding vignettes, where characters give a long rambly talk about their lives and circumstances, connected mostly through the setting as opposed to a streamlined story. But that is certainly not a bad thing, in fact, that’s what makes the game so fantastic.

Conceptual Meta-Wank:

It’s not too uncommon for the overt threats in a horror game to distract us from the less direct problems in the world. After all, who’s going to care about the socioeconomic issues raised by the Umbrella Corporations influence while being chased by a Tyrant in Resident Evil? But with all good horror, the themes are there, and extremely important, and while they are frequently unnoticed, they can be what makes a horror game truly great. To Dawn and Back is especially good at laying them bare.

Without enemies to distract our lizard brains from the world around us, To Dawn and Back allows us to really hone in on what the true implications of the universe depicted mean. The strange panopticon society plagued with religious fanaticism and terrible poverty amplifies the conversations with a cheerful guy crucified or two people boning in an alley. The real unsettling feeling in To Dawn and Back comes not from the imminent fear of being chomped by a zombie, but from simply taking a moment to process the lives of the characters you may meet.

Non-Wanky Game Recap:

The gameplay loop for To Dawn and Back follows the day-to-day life of the protagonist. Waking up, leaving the apartment, searching for something to do while auntie is at work, and returning home for bed. This feeling of aimlessness that lasts about an hour makes the tonal shift feel that much more important. Decisions feel less arbitrary, interactions a lot more intriguing. The story starts to feel, in spite of the woah-what-is-reality theme, a lot more real.

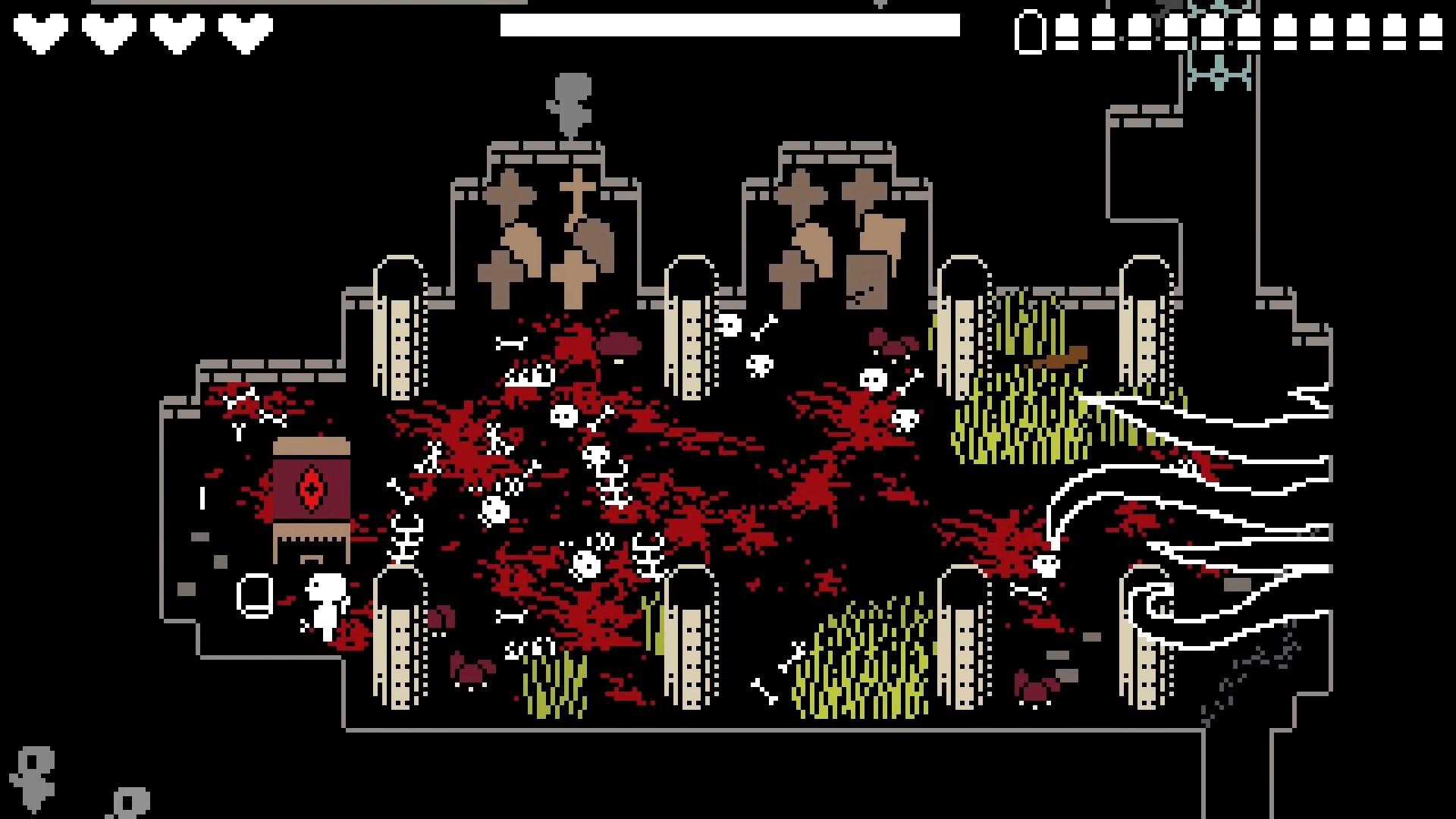

On top of that, the lack of gameplay actually works really well in this situation. To Dawn and Back is a simple game, which more or less does nothing new. Low poly 2.5D graphics, bizarre art, and minimal gameplay beyond walking and interacting with the environment. It’s not bad, in fact it kind of makes the experience that much better. Retaining the interactivity of a video game, while boosting the storytelling creates an experience that feels more like a real world experience instead of a video game. While I do always appreciate a game with Quake style bunny hopping or active reloads, simplicity in a narrative based game also goes a long way.

What Works:

I know I’m guilty of assuming that horror needs a spooky monster or jumpy scare. Good art evokes an emotional reaction, and fear is as good an emotion as any. But without any ghostie or ghoulie, To Dawn and Back relies simply on what you can read and see in this weird world. The grotesque citizenry and body horror are just one surface level layer of discomfort in a game with dark, real world themes. A guy with a hook through his jaw pales in comparison to the loss of loved ones, and the terrible reality of moving past that. This type of horror is atypical, but works because they are things we relate to on a spiritual level.

And yet To Dawn and Back works so well because it takes these themes to the extreme. The religious fervor determined to improve society ends up ruining the lives of most people in it. In so offering their services to the church, perhaps a stand-in for government or economic practice, they are literally turned into furniture or decoration. And to deny allegiance or acceptance of that zealous society means that you become the subject of the cruelest of punishments. This society turns all into helpless cogs in a terrible machine, and To Dawn and Back is not afraid to make the connections between the game and the real world.

What Doesn’t Work:

My problems with To Dawn and Back are few. Truthfully, both of these are kind of a stretch. The first is the aesthetic. I honestly love this style. The clash of bright red and turquoise is fantastic, and creating unsettling drawings to go along with the pixelated sprites is great. But, and I recognize this was probably an artistic choice, replacing the walls of interior areas with the black background of a skybox does not really work with the rest of the game. This is my personal opinion, but when you can see the back of an object from around the corner, ie the inverted side of a doorframe, it kind of messes with the immersion.

Additionally, the open world feel of the game mixed with the time limit made me feel obligated to check and double check that I didn’t miss anything during the day. The day cycle of To Dawn and Back makes it so that you must finish all your chores in the course of a day before you return home, otherwise you might miss encounters or even quests. I respect the open world elements, indeed, they are strengths. But a dum dum like me sometimes needs directions, otherwise I miss out, or, even worse, go in circles looking for something I missed.

How To Fix It:

Both of these seem like relatively easy fixes. The aesthetic of the inky black walls is great, my issue with it is that you can “see” through the walls into the back of other objects. Making some walls that are the same black color and putting them in corners should solve this, admittedly extremely minor, issue. As for the lack of direction, give To Dawn and Back an option for dum dums to be able to use a Postal style checklist. Bada bing bada boom fixed.

Wanky Musings

Not every game needs to be challenging. Not all horror needs to be from a life and death situation. That’s what makes To Dawn and Back so cool. On top of that, the visuals are great and the soundtrack is top-notch. And most of all, it’s emotionally resonant and super intriguing. To Dawn and Back is certainly a game I would consider to be art, one that could be enjoyed both by gamers and non-gamers alike. I think this is about as close to a Basquiat game as we’ll ever get. You can try out the game for free on itch.io by clicking here.