Mandatory Fear – The Devilish Mechanics of Sweet Home

Mandatory Fear is a look back at the vital entries in horror gaming, exploring what made them effective at scaring us and their importance to the history of the genre.

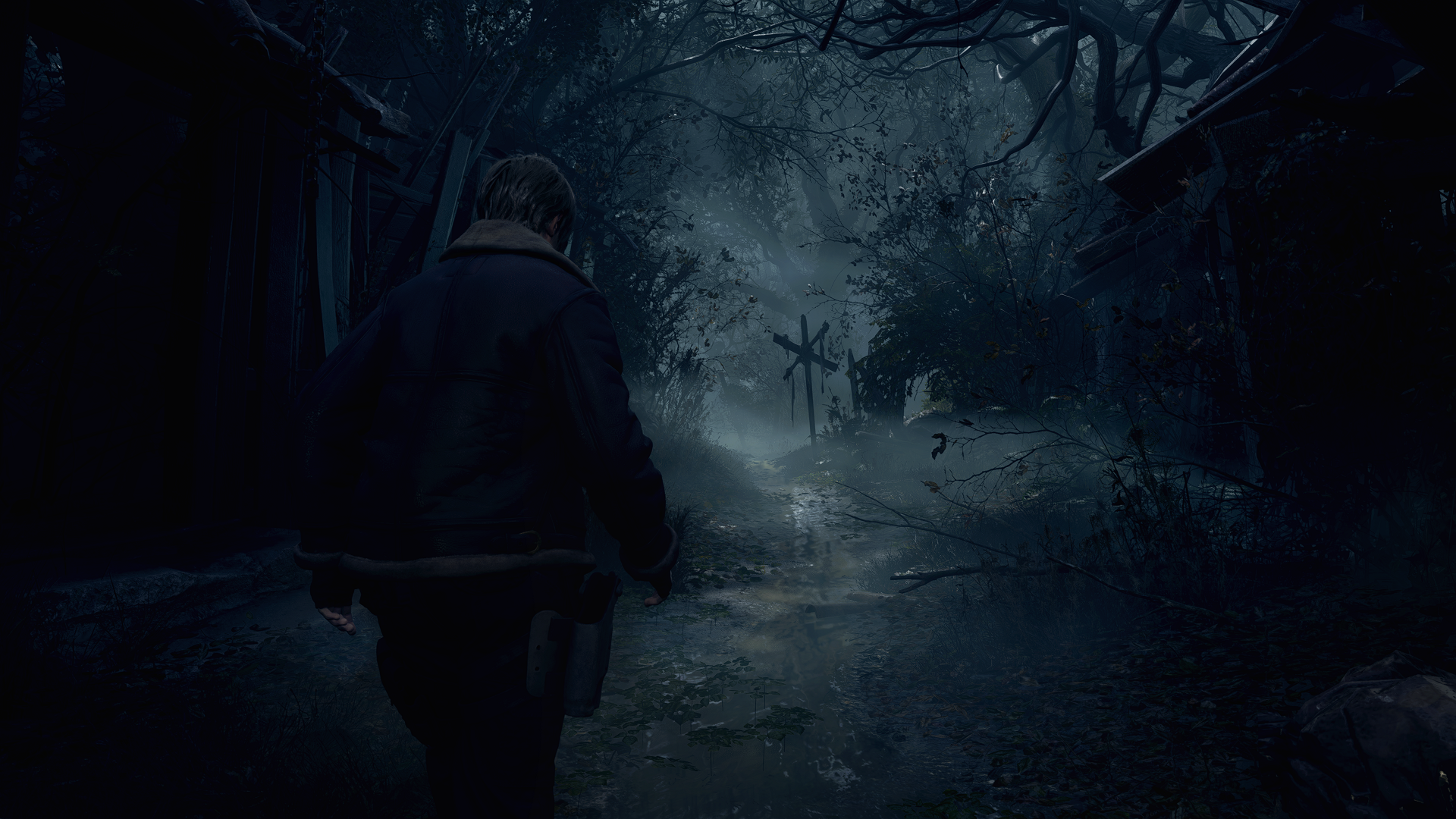

It is an incredible shame that Sweet Home, a Famicom horror classic, has never made its way out of Japan (unless you get industrious with fan translations and emulators). As a clear inspiration for Resident Evil, as a ruthless RPG where death is permanent and sickening monsters are plentiful, and as a master work in complex, twisted storytelling, it deserves to be more widely available.

If anything, it should be out there for all horror game fans because of its terrifying design, which paved the road for future horror titles and is still a shining example of how to make a frightening RPG. Through its extremely limited resources, finite healing, secret traps, its party mechanics, and its habit of killing your poor crew members forever, it makes for a tense journey through a mansion haunted by some of the most awful creatures ever rendered in pixels. It’s also probably one of the best games based off of a movie (in my opinion).

In Sweet Home, five film crew members have set out to document the frescoes of Mamiya Ichirou. These frescoes are in the abandoned Mamiya Manor, which has fallen into severe disrepair. While holes in the ground and some falling chandeliers (and entire rooms filled with quicksand) make the place pretty unsafe to move through, it’s more that it’s filled with all manner of pulsing ghouls and wriggling beasts. Guess you’d better hope this film crew is filled with skilled fighters for some reason.

It isn’t, though. But one of its members is good with a vacuum cleaner! That has to count for something, right?

Oddly enough, it does. Each of your party members has a specific function that makes them uniquely helpful. Asuka and her vacuum cleaner can clear broken glass out of your path (which is a big problem in a broken down manor, apparently). Emi has a skeleton key that will open most locked doors in your way. Ryō has a camera that can snap pictures of the frescoes, revealing vital plot aspects and clues as to how to progress. Akiko uses a medical kit that will cure many status ailments. Kazuo carries a lighter that can burn things blocking your path, or light candles to see in the dark. All of them serve vital purposes throughout the game through these items.

Now that Sweet Home has made each party member valuable in some way, it gets you to split your party up to travel around with them. You can divvy them up into groups of one, two, or three members, and will have to swap between groups to get around the mansion safely. This means that you’re often guessing at who you should bring with you, resulting in many moments where you’ll wish you’d brought someone else along with you because you need their item. While that can get annoying, this party splitting works well as a horror element in that it forces the player to constantly balance how strong they want the party to be.

For the most part, you’re forced to make a three person and two person party, somehow balancing both for combat situations. This means carefully juggling your weaker and stronger characters (each has varied combat proficiencies) as well as the better weapons each party carries. One party is always going to be a bit weaker than the other, making every journey with them feel a bit more tense. Also, as you’ll need specific items in certain situations, you have to gauge whether it’s worth the risk to send the exact party members you need, even if they’re kind of weak together, hoping you don’t get into a random battle.

The alternative is a lot of long trips with two parties, which increases the number of battles you will likely get into with both. Thankfully, Sweet Home gives you the Call ability, which eats up a turn but gives the other party a short window to run to the combat party and enter the fight with them. It’s one the very few kindnesses this game affords you, so use it.

If you’re thinking there isn’t much downside to getting in more fights in an RPG since you’ll be accruing experience and getting stronger, you’re right…sort of. Enemies do give you the experience you need to level up, but the game does not have much in the way of healing, so each hit you take is a big deal. It only has one type of healing item, a tonic that cures your party fully. It sounds like a great item, except that they are very limited. There’s twenty-one of them in the entire game, actually, which means you can only fully heal yourself that many times.

Since healing is limited, you’re going to want to take some risks in combat. Maybe let your hit points get a bit low before you decide to heal so that you make the most of your curative items. Doing that puts you at risk of permanent death in Sweet Home. If a character gets to 0 hit points, they die forever, leaving a corpse on the map that you can thankfully pick over for items. Even a single death puts a huge dent in your combat power, making your life that much more difficult as you progress through the game.

These elements together make every fight feel terribly intense. Monsters hit hard, frequently having status ailments that can really mess with your party (one will make every party member strike the afflicted member instead of the monster, which is a REAL TREAT). You’re going to want to keep everyone healed to avoid dying, but healing is finite, so you have no choice but to risk it at times. And you can’t just avoid fighting as the monsters are always getting stronger as you progress, so you’re forced to face these frightening combat situations all the time, and often with weird party makeups where you can’t rely on your heaviest hitters. Even your status ailment healer might be outside the party, forcing you to waste turns using Call in hopes that she can get to you before you beat your own friend to death.

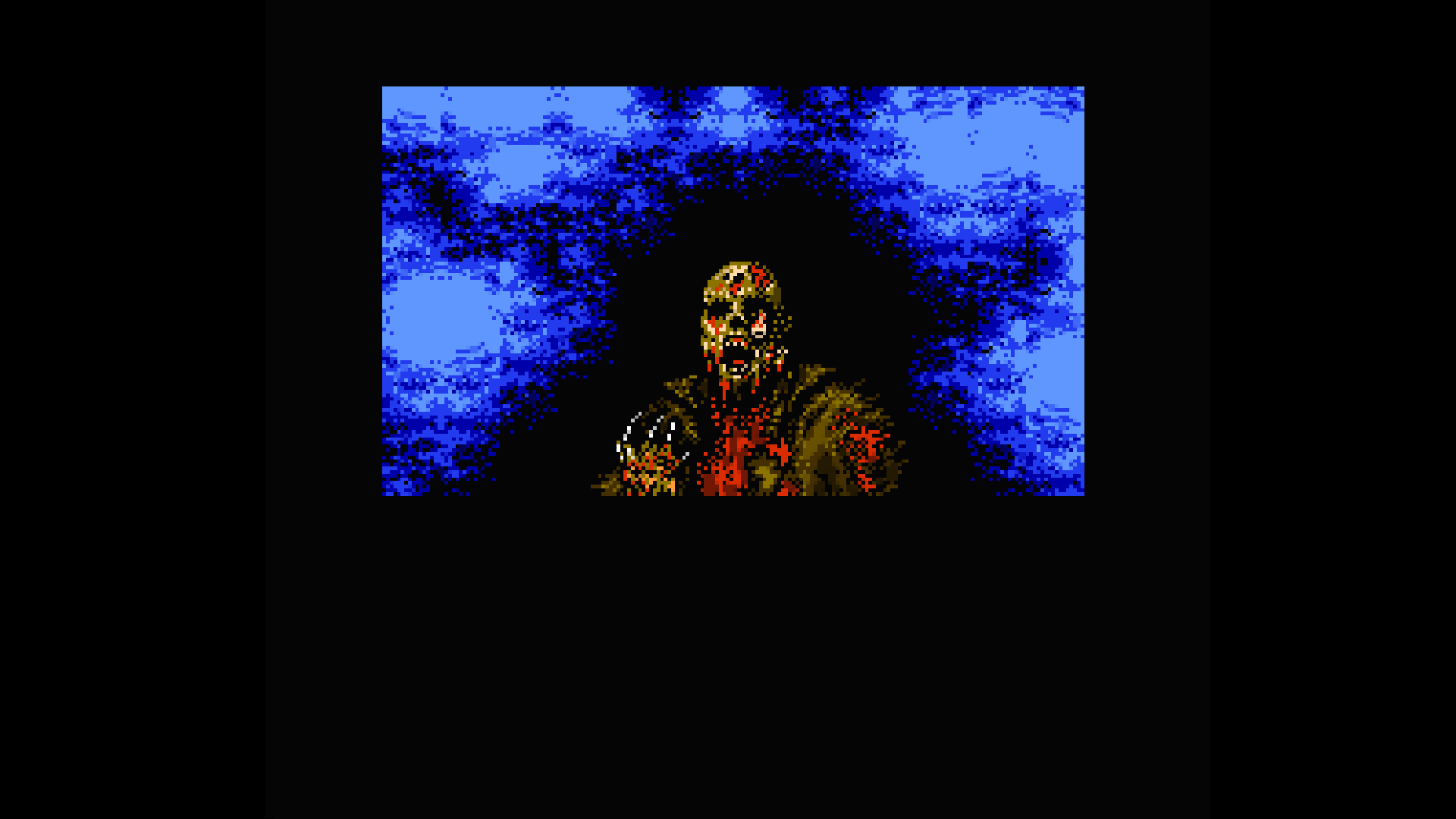

Adding to this tension is the game’s visuals and sound, which make for some gruesome sights and unsettling music for its era. Monsters quiver before you, sores pulsing across their decaying skin. They vomit up their own insides, or wriggle against the ground. They’re all incredibly off-putting and menacing for stuff created on the Famicom, adding a revulsion to combat that makes you just want to escape them. Sweet Home’s soundtrack, filled with droning, disturbing tones, constantly drags out a sense of discomfort as you explore, while it’s high-energy battle track feels like it wants you to run away from the dangers you’re facing.

It’s the splat sound that the game makes when one of your female characters hit the ground, dead (the men have their own unique death), and the sight of their body being dragged back, smearing blood across the floor, that shows the power of these visuals and sounds. This moment strikes hard, making for one of the most abrupt, disturbing deaths I’ve seen in games, something that is absolutely monumental for having been done in 1989. It also makes it very clear that you’ve screwed up badly and are now in huge trouble.

Now, or in the moments when you hopefully healed yourself to avoid this, are when Sweet Home‘s sharp item mechanics come into play. Each character can carry a weapon, their item, and two additional things, and that’s it. Given that you often need candles for light, boards to cross holes in the floor, rope to fish friends out of danger, tonics to heal your wounded allies, and several other key things, you’ll quickly fill up your inventory, having to choose between healing and items you need to progress (and again, your party member with the vital item might not be in the right party). You’re constantly making difficult decisions about what to carry and who to give it to.

This problem is compounded by the fact that there is no item box or anything to allow you to pick up and store items. Anything you can’t carry will stay wherever you drop it or leave it, meaning that those valuable tonics could be scattered all over the dungeon because you didn’t have room to pick them up, or some valuable item will be way across the manor because you didn’t see a use for it at the time. This means more walking, which means more fights, which means more damage, which means you’re in that much more danger. It’s an ingenious system that has you stressing over which things to carry and what to leave, and will have you scrambling across a haunted house to find that last precious tonic you left waaaaaay back somewhere. Assuming you remember where it is. The game doesn’t keep track for you.

And if you let someone die? Well, each person has an item you need to progress, if you’ll recall. There are replacement items in the mansion that will let other characters use those abilities, but these naturally eat up one of your precious item slots. So, not only are you down a valuable fighter, but you have to waste one of your item slots on carrying an item to replace them.

What if you’re especially careful in combat and with items, though? Well, the game is also filled with traps that can chew through your hit points, send party members off by themselves, or kill a party member in seconds. Sweet Home has very little interest in playing fair with its players.

Falling objects are a small worry, as they give you a few seconds to choose a direction to dodge in (although I found it was pretty random whether I would actually avoid damage). Still, if you’ve been limping about at low hit points, a fallen chandelier or thrown dagger might be the end of one party member. Spiraling spirits are a bigger worry, as these glowing, moving lights will grab a single party member and carry them off somewhere else in the mansion, forcing you to retrieve them. Again, this increases the damage you’re likely to take over time. It’s worse if you get cocky and try to make that individual member walk back to the party. Never make a party member explore alone in the game if you can avoid it.

Quicksand or pit traps are Sweet Home at its most cruel, though. You can literally step into a room and find yourself falling into a pool of quicksand, requiring another player to get you out. Likewise, the majority of the boards you use to cross pits have a finite amount of times you can walk across them before they break, requiring a rescue. If you aren’t quick in these situations, the fallen character will die. Given that these moments tend to happen by surprise, you’ll typically find yourself panicking as you scramble to save them. Now, even walking through a door (which always comes with a door-opening cutscene that will be delightfully familiar to Resident Evil fans) or crossing a pit comes with a sense of danger, adding even further tension onto the player.

If that’s not enough to make for an excellent experience in fear and tension, Sweet Home also has one of the most chilling stories I’ve experienced in horror. I don’t want to spoil why Lady Mamiya is haunting the mansion and trying to kill your party, but the reason, as well as the story behind it, is deeply disturbing, coming together through fragments of story told on notes and within the frescoes you discover in the mansion. It requires some thought and care to put the story together, involving the player in discerning the narrative in interesting ways while also setting the groundwork for how much of horror would tell its stories in the future.

All of these things work as a millstone, steadily grinding the player down by creating anxiety and tension through making combat and exploration incredibly lethal while giving them very few tools to deal with it if they aren’t careful. The mind swirls with your various needs as the game keeps asking you to take risks to keep progressing. You’re continually forced into deadly situations to keep moving, but your limited inventory, fractured party, and steadily-draining health mean a mistake is almost inevitable. Compound this with traps and you cannot help but spend every moment of this game worrying about what will bring about your doom.

It’s incredible that a Famicom-era title could use all of these mechanics to create a deep fear about the well-being of your party and the permanence of failure. Keep in mind, this is still a long RPG. Maybe not Final Fantasy-long, but still a good fifteen to twenty hours if you don’t know it inside and out. That’s a lot of progress to lose if you die, something that will have you worrying about your party’s well-being the entire time you play.

Combine this fear of death and a worry about your steadily-dwindling power with the game’s dreary, draining music, sickening art style, and a gut punch of a chilling story and you have the makings of an incredible horror game in an era where the genre was barely getting started. Sweet Home is a feat of narrative and design for its time – a title that still has plenty to teach modern horror developers, and an experience that any horror game fan needs to try out.