How Can You Make a Pistol Feel Powerful in a Horror Game?

Pistols hold an odd place in the collective arsenal of survival horror weapons. Often the first weapon the player acquires, they usually become a victim of redundancy as the game progresses. You know it goes; first you’ll get the pistol (after maybe acquiring the game’s token melee weapon), then the shotgun, then the machine gun, then the sniper rifle, then the special weapon you’ll spend the entire game saving ammo up for, and finally the phased plasma rifle in a 40-watt range when the game jumps the shark and goes full action. In these cases, the pistol becomes little more than an afterthought, used only out of necessity rather than out of player choice, and totally irrelevant by the mid-game if not sooner. Players only begrudgingly hold onto them out of a fear of running out of ammo for their flashier guns, or simply because the game won’t allow them to drop them.

It’s a shame when this happens, because as a choice of firearm pistols are ideally suited to the themes and tones of survival horror. They’re close quarter weapons that usually have a relatively restricted magazine size, making them perfect for tense, up-close-and-personal combat encounters where each shot counts. Just as importantly, they’re also weapons with a limited degree of utility, employed as back up weapons that couldn’t hold their own in a serious, extended firefight. We’ve all seen those movies where our heroes are up against a wall with only a handgun left; their main weapons either lost or out of ammo, forced to rely on their sidearms as the monsters close in.

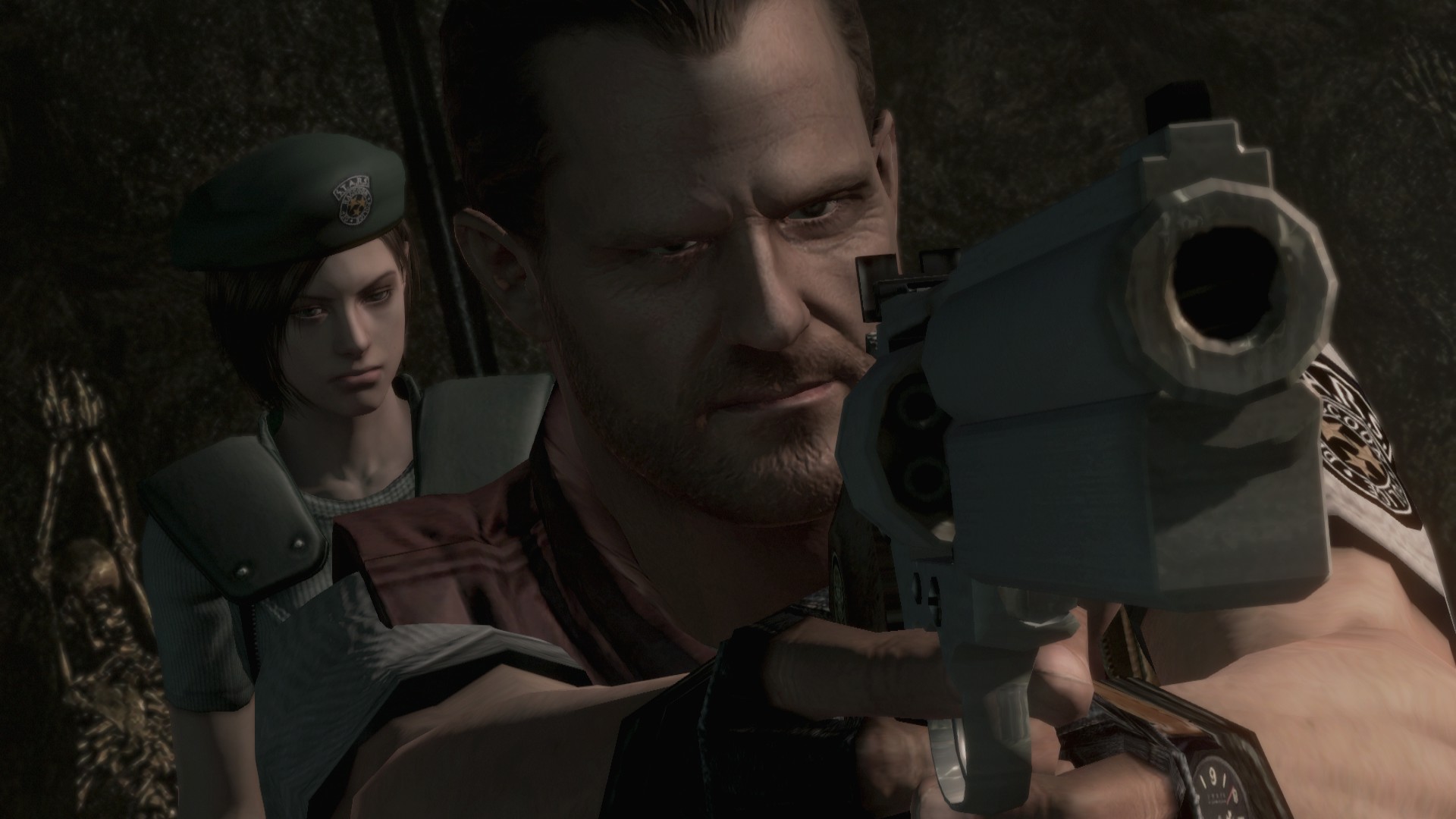

The first Resident Evil managed to capture this feeling perfectly. The S.T.A.R.S. team sent out to the Arklay Mountains are woefully under equipped for the horrors they’ll encounter, driven into the Spencer Mansion by a pack of zombie dogs and (initially at least) packing firepower not much more powerful than that of an average beat cop. Imagine the situation if every member had been equipped from the outset with an assault rifle. Even if it functioned equivalently to the pistol, and even if everything else about the game had been kept the same, I can still virtually guarantee that the whole experience would have felt very different.

Perhaps this is the root of the issue. Because pistols aren’t generally as powerful as long guns in real life, the natural inclination many games seem to take is to just treat sidearms as inferior versions of their larger cousins. From a design point of view, they’re treated as points on a linear curve of progressive player empowerment, with obsolescence built into their design as a result. That sounds a bit academic, but three very good (or rather, bad) examples illustrate the idea. Bioshock, Doom 3 and Half Life 2 all had pistols as the first firearm the player acquires, and in all three of these games they’re at their most useful when the player has no other choice of weapon. As soon as you get the game’s next gun (the shotgun in Bioshock and Doom 3, and the SMG in Half Life 2), the pistol’s utility diminishes considerably. From then on, this trend only becomes more noticeable the more weapons you acquire. And why not? There’s nothing about the pistol in these titles that set them apart from the other guns. They’re inferior solutions to the same combat problems, whose shortcomings become more and more apparent as the challenge ramps up. By the time I’d acquired the shotgun, Tommy gun and a few plasmids in Bioshock I’d stopped using the revolver for anything other than taking out security cameras and turrets; for Half Life 2, the pistol was relegated to Barnacle and red barrel duty, if that. And I struggle to think of a single time I used the pistol after acquiring sufficient shotgun ammo in Doom 3.

Probably the worst instance of this I can think of is 2016’s otherwise stellar Doom. Here the pistol didn’t just feel weak in comparison to other weapons; it just felt weak full stop. As well as looking and sounding like a Fisher Price toy, even taking out a basic zombie with this gun took far too many rounds than it should of, and, barring completing a few challenges, I can’t imagine any player used it much if at all beyond the game’s first level. It seems that the developers themselves realized the problems with the weapon, as it was dropped from the campaign entirely when it came to Doom Eternal.

Pistol Whipped

There’s a number of ways games can go about solving the problem of sidelined sidearms. Part of the solution definitely lies on the art side of things. Making a gun ‘feel’ weighty is just as – if not more so – important as a gun’s objective stats. Maybe it’s just me, but I can’t help but feel like a number of the recent Resident Evil games – particularly the Resident Evil 2 remake and Resident Evil: Village – had pistols that just sounded a bit tinny and weak, a shame, given how much you had to rely on them. The original Evil Within had a number of problems (for one thing, its survival horror level of ammo distribution in a game that was predominantly action horror), but something it did nail was the weapons, with the revolver having a nice, solid crack to it that made it a joy to shoot.

Yet the core challenge is one of design. Survival horror games offer a simulacrum of reality, not a simulation, and as such designers shouldn’t necessarily be constrained by real-world limitations. Instead, they should see every gun as a different instrument in the player’s toolkit, each offering something different. Here are three ways that pistols can stand out from the crowd.

Solution 1: Pistols as an Answer to Ammo Scarcity

In horror games where resources are generally thin on the ground, pistol rounds are nearly always the most common type of ammunition. In these cases, larger guns tend to become secondary weapons until the late game, held in reserve by the player to take out more powerful enemies or large mobs. This is probably the most common way horror titles try to keep pistols relevant, and works best in games where combat is as much about resource management as it is about the combat itself. The early fixed camera, tank control survival horror titles are probably the best example of this concept in its purest form. Since these games lacked the interactivity of full 3D aiming, combat was more or less relegated to simply readying a weapon and firing in an enemy’s general direction. As a result, these games made moment-to-moment combat only an aspect of longer-term ammo and health management. The real challenge wasn’t taking out the enemy in front of you; it was about knowing which ones to take out, and when, and having enough bullets to do so. Pistols were an important part of this system, because although objectively weaker, their more plentiful ammo allowed players to horde their heavier ordinance for crucial encounters like boss battles.

This design choice needn’t be relegated to fixed camera games. Modern entries in the horror genre, such as the recent Resident Evil remakes and Alien: Isolation, have shown that this tactic can work just as well with fully fleshed out combat systems. If there’s a drawback to this process, however, it’s that it often involves more stick than carrot. Players will use their sidearm not necessarily because they want to, but because they’re afraid of running out of ammunition for their better weapons. It may also be a contributing factor to that jarring feeling you get when horror games sometimes go full Rambo in the final acts. Previously scarce ammo becomes abundant as you’re bombarded with enemies, leading to a disconnect with the earlier experience. Whereas before you’d held on to those precious few shotgun shells and dutifully used your pistol, now you’re getting whole cartons of buckshot in every new room, making all that prior restraint feel disconnected from the present experience.

Solution 2: Pistols That do Something Unique

Keeping sidearms relevant by making their ammo more common than other guns isn’t necessarily a bad tactic. But if this is the route designers go down, it’s arguably better to include a positive incentive to use pistols as well. One obvious way to do this is to have a game’s pistol be able to do something that no other gun can. Dead Space’s Plasma Cutter is a great example of this. Whilst every gun in the game has an alternative fire mode, none are so versatile as the Plasma Cutter’s ability to change the angle of its beam. Despite not being the strongest weapon in Isaac’s arsenal, this function allows for much more precise Necromorph dismemberment than any other weapon, and is so useful that you could happily complete the game without needing to rely on any other tool.

Another great example are the revolvers from the criminally underrated PS2 game Darkwatch. Set in an undead infested Wild West, the game featured weapons that put unique spins on conventional cowboy guns. Two of the standouts were the Redeemer and the Warmaker pistols; bladed revolvers that could be fired so fast that they practically became proto-SMGs. Since all the other weapons relied on manual cycles to work each round (such as lever-action rifles and pump shotguns), these sidearms held their own thanks to their significantly higher rate of fire.

Solution 3: Pistols as a Jacks of All Trades

Making pistols do something unique is an idea that can be taken to a more conceptual level. In real life, a semi-automatic 9mm pistol may have an objectively lower rate of fire and caliber than a fully automatic assault rifle. But if these two guns are used in a game, it doesn’t follow that one should be straightforwardly weaker than the other. As I’ve said already, weapons are tools that a game gives the player to let them overcome the challenges it presents. In horror games, guns tend to fall into archetypal categories; the pistol, the shotgun, the machine gun, the sniper rifle, and so on. Because of this, each can be tailored to dealing with a specific type of combat encounter, with each weapon having its own strengths and weaknesses.

Resident Evil 4 is hands down one of the best examples of a survival horror game using this principle. I struggle to think of any other horror game where each weapon has been so finely balanced not just in its own stats, but in comparison to the wider arsenal, something especially impressive when you consider just how many guns the game has. Each type of weapon had its own very clear pros and cons. Shotguns and magnums were the game’s heavy hitters; ammo for each was relatively scarce, but they could be relied upon to stagger tougher foes that could shrug off other rounds. The TMP was good for crowd control, but was poor against enemies that could soak up damage. Sniper rifles were designed for long range shooting, but their scoped views made it very easy for the player to get blindsided if they weren’t careful. And the Mine Thrower… well, the Mine Thrower was a bit of an awkward weapon, but it was still fun to use in certain situations.

But what about the handguns? The genius of Resident Evil 4’s design here was their versatility. Whilst they couldn’t match other firearms in their specific area of expertise, they made up for this by being able to perform multiple roles. Generous magazine sizes let players hold their own against crowds, well placed shots could crit or stagger enemies, and even at range high accuracy shooting was possible. The game went one step further, introducing different handguns that appealed to different playstyles. The Blacktail offered a rapid rate of fire, the standard handgun’s upgrades made it ideal for players aiming for headshots, and the Red9 traded rate of fire for impressive damage per shot. Rather than being outclassed by other weapons, the handguns of Resident Evil 4 served instead as vital counterparts to them, acting as counterbalances to their flaws.

Packing heat

Any game weapon should always be thought of in holistic terms. Rather than just looking at what a gun does by itself, designers should consider how it compares to and interacts with the player’s wider arsenal. This is especially important for survival horror, where the damage each gun does and the amount of ammo available to it are crucial factors in getting a horror experience right. Pistols often get the short end of the stick in these scenarios, but if designers as treat them as the equals of larger weapons, rather than their subordinates, it can go a long way to making a much stronger game overall.